Last weekend, I had the opportunity to attend the Queer Fashion History Symposium. I spent six and half hours preparing for this event. Three minutes checking in with my editor for the event, 55 minutes looking for my press badge, two minutes watching my boifriend find my press badge hanging from my doorknob, 30 minutes dropping off my favorite pair of boots at Phillips Shoe Repair, 30 minutes spilling the tea with my favorite shoe repairman’s wife, 30 minutes re-adhering crystals to my favorite pair of boots, four hours deciding on approximately three outfits to match my favorite pair of boots. In case you are wondering, yes dear, these boots are everything!Arriving at the symposium with my boots and badge in tow, I scanned the room with an immediate furrowed brow. I had imagined wild hair under elaborate chapeaus, statement necklaces and new romantic inspired street fashion. Instead I saw almost exclusively plain shoes, muted colors and dulled accessories- perhaps foreshadowing the day to come.

I watched in horror as panelists and speakers discussed the road of fashion that lead us happy homos to where we are today, erasing all color except to mention Janelle Monae’s tuxedo and Rupaul’s “fascinating” transformation into high femme drag. Then came perhaps the truest heartbreak: the portrayal and iconography of the Dandy as one of white celebrity and wealth. Using none other than Oscar Wilde, we were regaled with tales of Wilde’s commitment to dandy attire and general representations of gay flagging with pops of color in pocket squares and socks or the peacock suit movement of colored suits. We listened to tales of Parisian androgynies in the early 20th century engaging in dapper dykery at bars like La Monacle, rounding out with devotionals of Marlene Dietrich in her Dior suit.

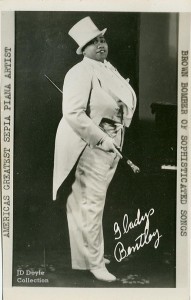

In all, no mention of Ma Rainey, Gladys Bentley, or Josephine Baker who in the early 20th century, and throughout the Harlem Renaissance, were singing jazz, blues, and leading bands in men’s tailcoats, top hats, ties, and cufflinks. There was no mention of the Congolese Sapeurs and flamboyant French-African suit wearers and makers who, since the 18th century, have been creating and maintaining the code of Dandyism. These Afro-Dandies, most of which have survived two brutal and devastating civil wars, use their brightly chic attire and mottos like, “let’s drop our weapons and dress elegantly,” to create a gentile lifestyle of poise and charm.

How is it that these folks have been forgotten? How are they not even a footnote in the stories written for and by them? Why has the story of our queer fashion, the fashion that has quite literally shaped the way the world adorns itself, been bleached and abbreviated?

The answer is in the vise of Simon Doonan, who while discussing his obsession with designers who died of AIDS in the early years of the plague, explained he didn’t want them to be forgotten. Surely, if I’ve learned anything from this walk down memory lane, it’s the reminder that not only will no one tell our quaintly queer stories for us, but we also are in constant danger of swiftly being written out of the history that remains.